BREATH

"The music actually starts before we hear any sound." – Roger Bobo

"The music actually starts before we hear any sound." – Roger Bobo

"Why Do You Breathe?"

Joe Alessi asked an interesting question during a masterclass. The answer never emerged – the class took a different direction, but it got me thinking. There are several reasons:

It’s best if the audience thinks all breaths are phrasing – punctuation: commas, periods, exclamation points, etc. There are phrases within phrases, within . . . If you’re out of gas, you have to breath – but sell it as a phrasing choice. Listen to different great actors read the same poem; there are many, many, ways to read it. And the audience is subliminally “breathing” with you. Sometimes you can create a great effect by making them “hold their breath” but generally, fulfilling their expectation is good. This is clearly more of an issue on bass trombone than tenor. I remember one of my favorite 1st trombone players saying, "Hey Bob, we're all gonna breath right here." I said, "Have fun with that; I will have breathed about 5 times by then – but I will breathe there with you."

Read what Roger Bobo had to say about Breathing.

- Staying alive (always a good idea);

- Re-supplying “fuel” for tone production (which relates to number one); and

- Phrasing!

It’s best if the audience thinks all breaths are phrasing – punctuation: commas, periods, exclamation points, etc. There are phrases within phrases, within . . . If you’re out of gas, you have to breath – but sell it as a phrasing choice. Listen to different great actors read the same poem; there are many, many, ways to read it. And the audience is subliminally “breathing” with you. Sometimes you can create a great effect by making them “hold their breath” but generally, fulfilling their expectation is good. This is clearly more of an issue on bass trombone than tenor. I remember one of my favorite 1st trombone players saying, "Hey Bob, we're all gonna breath right here." I said, "Have fun with that; I will have breathed about 5 times by then – but I will breathe there with you."

Read what Roger Bobo had to say about Breathing.

Some Thoughts on Breathing for Low Brasses*:

- SILENT inhale!

- Feel air activity/motion/friction (both in and out) at/on the lips – not inside your mouth or body.

- Don't get all the way full nor all the way empty – too much tension (scroll down).

- Bass Trombone always sounds better on comfortably full lungs.**

- Don't make some elaborate facial expression to inhale. "It take 43 muscles to frown, 17 to smile, and ZERO to sit there with a stupid look on your face, which is how I want you to inhale."*** (Not strictly accurate, but a good image.)

- Don't actively open your mouth, just let your face go limp – "novocaine-face" – gravity is your friend. Let your face rest a little on every breath – and get more air with less effort.

- The trachea is ca. 1⁄2 to 3⁄4 in in. diameter, there is no point in opening the mouth more than that – it can be counterproductive.

- Allow a little air in through your nose – less mouth opening.

- Keep the mouthpiece on your lips, inhale around it.

- Don't gasp! Slow air = more air.

- If you have time: sigh first – and take a long, slow, relaxed, comfortable, breath.

- If you don't have time, take a quick, relaxed, half-breath – before you get too empty.

- Let the exhalation start by relaxing, then add a little effort as needed (don't get empty – too much effort/tension). Same with inhalation. The body's elasticity**** will do much of the work (see below).

- Don't "belly-breathe" – allow your body expand and contract in all possible directions.

- Don't "set" your abdominal muscles – allow them to do what they need to do – focus on the result – air motion – between the lips.

- Don't let the air motion stop between inhalation and exhalation or exhalation and inhalation – just change direction. Imagine a pendulum – it may look like it stops, but it just slows down, and changes direction – instantaneously.

- Don't "blow" – FLOW!

See Valsalva Maneuver

*Playing a "Dubba-Hi Q" may different.

**John Rojak has said, "I take a full breath for a short note."

***Bob Sanders, ca. 1982

****The sad truth is elasticity diminishes with age. So it goes.

Let's discuss activity/motion/friction at/on/in front of the lips. The smallest point in the "tube" that goes from the lips to the lungs creates a venturi. If that is surrounded by soft tissue, the lowered air pressure will "suck" the opening more closed, increasing the venturi effect, compounding the problem. If the smallest point in the system is at the lips, it's size can be controlled – not so much back in the throat. Arnold Jacobs said, “The valuable part of this is that you are sensing the inspiration at the mouth. This is where the inspiratory control should be, at the lips. We never want more space at the front of the mouth than the size of the pharynx, otherwise you will have a primary friction to the entrance of the throat. This one gets very hard to control, this one does not.”

David Brubeck’s (the bass trombonist, not the famous jazz pianist – his cousin) excellent 5-part series, The Pedagogy of Arnold Jacobs, (check it out) points out, “While some believe that Mr. Jacobs advocates a full breath, that is not precisely the case. He advocates a comfortable breath, or about eighty percent of one’s vital capacity.” This strikes me as very similar to Emory Remington’s “conversational breath” or Joe Alessi’s “doctor’s office breath.”

Roger Bobo has said not to use the bottom third of vital capacity – except in emergencies.

Will Kimbles article, 10 Proven Ways to Improve Breathing, discusses many things I agree with. One is "Take big breaths, even when you don’t think you need them." (but not too big – "comfortable" – 80%)

David Rejano has written ("Full Access" is required for more than the "Abstract" – $3.99 per month for all the brass stuff) something very interesting: "We need a certain aperture in order to produce this vibration: a small gap between our lower and upper lip. This fact negates the popular advice, 'You must use warm air to play the trombone.' You can experiment by opening your mouth like you are about to yawn and putting your hand in front of it. Let the air out like you are fogging up a bathroom mirror; the air is warm. Now, make your lips as if you were going to whistle, similarly to an embouchure, and put your hand in front of your mouth once more. Blow air through the tiny gap between your lips; the air is cold." I agree. Another major posaune pedagogue in the days of yore (whom I can't remember) suggested "warm air" (like fogging a mirror) involves closing the glottis. You can reverse the experiment and observe. I feel keeping the air activity/friction at the lips – both in and out – is vital. See About Buzzing.

This lady clearly loves Jussi Björling (as do I, as did Pavarotti and Bud Herseth). Her analysis is interesting generally – and there is a GREAT lesson on inhalation at 10:24 – check it out.

This video is just excellent. It is however, merely a 1-minute sample. The full 9-minute video – with profoundly informative narration – in several languages – can be purchased from it's creator, Jessica Wolf, for a very reasonable fee. It is the best I've seen and well worth it – if one is interested in respiration – and most of us should be!

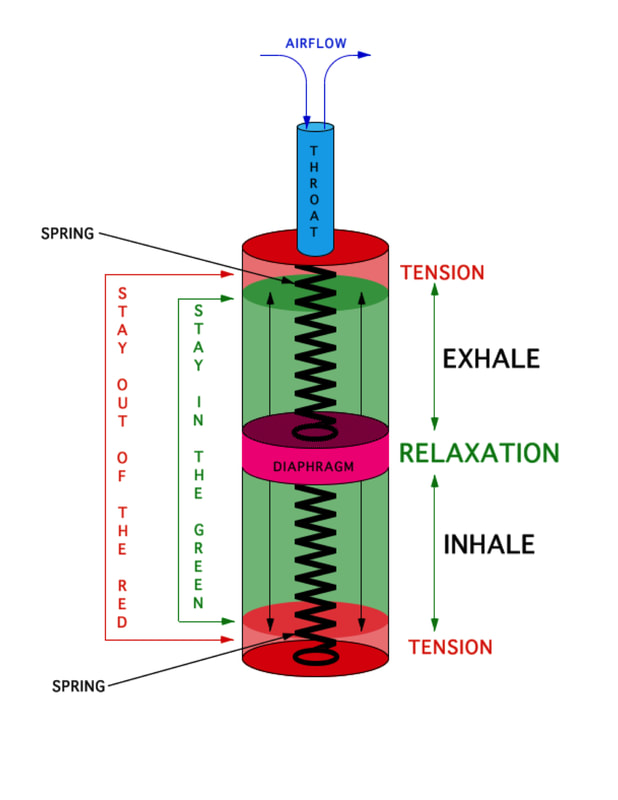

Most skeletal muscles work in opposing pairs; when one contracts, the other relaxes. This is true of the muscles of respiration. The diaphragm is the principal muscle of inhalation. In my primitive, fanciful, illustration below, it is visualized as a piston in a cylinder (and springs representing elasticity). This image can be useful. When the system is relaxed, it is at midpoint.

Muscle type and innervation of the diaphragm is very interesting (to me, YMMV): "When it [the diaphragm] is contracted, our abdominal organs are pushed down and our abdominal walls are pushed out. When relaxed, this reverses. To exhale fully, it requires us to contract the abdominal wall muscles and the intercostal muscles (between the ribs) since our diaphragms can not move any higher than fully relaxed."

A muscle’s only action is contraction. When inhalation muscles contract, exhalation muscles relax and stretch. The elasticity of those muscles is sufficient to commence exhalation; when “midpoint” is reached, some contraction by the opposing muscles must be added. When exhalation is complete, the process reverses – again led by elasticity and relaxation – IF – one allows it.

If one gets too full or too empty, excessive tension is created; hence, Mr. Jacobs’s advice. If one avoids the bottom third, per Mr. Bobo, respiration remains relaxed. That said, explore the extremes to "widen the middle path" – but stay in the middle of that road – except in emergencies.

Edward Kleinhammer said, “Breath like they vote in Chicago: early and often.” If one frequently “tops off the tank” with small breaths – well before the bottom third, inhalation is quick and effortless. It is unnecessary to drag the air in, “kicking and screaming” – it will come back seemingly on its own accord due to elasticity. The first seconds of this video are instructive, too.

In Grabbing the Bird by the Tale: A Flutist’s History of Learning to Play, Alexander Murray, former principal flute with the London Symphony and Covent Garden Opera and Alexander Technique teacher, has written, "I found that I was able to play a loud, continuous section of the first Allegro in the [Beethoven] 7th Symphony without being aware of 'taking a breath.' The breath was returning in the brief intervals between the rhythmic figures. . . . the breath returns with a sort of elastic recoil."

I teach three basic breaths:

*Arnold Jacobs spoke of "maximum suction with minimal friction."

This is way easier than any of us try to make it!

Muscle type and innervation of the diaphragm is very interesting (to me, YMMV): "When it [the diaphragm] is contracted, our abdominal organs are pushed down and our abdominal walls are pushed out. When relaxed, this reverses. To exhale fully, it requires us to contract the abdominal wall muscles and the intercostal muscles (between the ribs) since our diaphragms can not move any higher than fully relaxed."

A muscle’s only action is contraction. When inhalation muscles contract, exhalation muscles relax and stretch. The elasticity of those muscles is sufficient to commence exhalation; when “midpoint” is reached, some contraction by the opposing muscles must be added. When exhalation is complete, the process reverses – again led by elasticity and relaxation – IF – one allows it.

If one gets too full or too empty, excessive tension is created; hence, Mr. Jacobs’s advice. If one avoids the bottom third, per Mr. Bobo, respiration remains relaxed. That said, explore the extremes to "widen the middle path" – but stay in the middle of that road – except in emergencies.

Edward Kleinhammer said, “Breath like they vote in Chicago: early and often.” If one frequently “tops off the tank” with small breaths – well before the bottom third, inhalation is quick and effortless. It is unnecessary to drag the air in, “kicking and screaming” – it will come back seemingly on its own accord due to elasticity. The first seconds of this video are instructive, too.

In Grabbing the Bird by the Tale: A Flutist’s History of Learning to Play, Alexander Murray, former principal flute with the London Symphony and Covent Garden Opera and Alexander Technique teacher, has written, "I found that I was able to play a loud, continuous section of the first Allegro in the [Beethoven] 7th Symphony without being aware of 'taking a breath.' The breath was returning in the brief intervals between the rhythmic figures. . . . the breath returns with a sort of elastic recoil."

I teach three basic breaths:

- Initial breath (or any breath with ample time) – a long, slow, silent, relaxing, breath – as though preceding a sigh. NOTE: sighing before the initial breath can facilitate elasticity.

- Replenishment breath – comfortably full – usually in rhythm – strive for a silent breath. Most students do not utilize all of the available rest. Don't stop the air motion. In – out – in, not in – hold – out – hold – in. If you don't hold, you get twice as much air in the same amount of time. And, if you have an eight rest, suck* a full, tenuto, eighth note – use all the rest – don't waste time!

- Elastic recoil – instantaneous – "non-breath" – just open your mouth – some breath will return by itself – if you let it (and breathe early & often enough). Remember: don't gasp – slow air is more air!

*Arnold Jacobs spoke of "maximum suction with minimal friction."

This is way easier than any of us try to make it!