Thoughts On "Projection"

This is a paraphrase, from memory, from a lesson with my great teacher, Jeff Reynolds, a long, long, time ago, quoting Tommy Stevens: "Our part is usually not as important – out front – as we think it is."

Ed Kleinhammer once told a student: "If you heard me, I was a failure. You shouldn't have heard a trombone player. You should have heard a great orchestra." – Food for thought.

Another paraphrase from Jeffrey: Frequently, we blend undetectably – below the "texture line." Sometimes, we are noticeably present in the blend – right at the "texture line." And sometimes, we are over the top – very occasionally, way over the top! Remember, Stan Lee said . . .

"Projection" is not necessarily about playing loud. George Roberts was notorious for playing very quietly and bleeding on every mic in the room – or cutting through a roaring big band. Barrett O'Hara (a great bass trombonist in his own right) attributed this phenomenon to the "magic burr" in George's tone. Tommy Johnson called it the "mystery tone." Jeff Reynolds tells a tale about working with George in his response to question #8 in David Brubeck's 2015 Seven Positions interview. And at Lloyd Ulyate’s 70th birthday party, Lew McCreary (another fine player) introduced George by saying, "Here's the only guy who can play the bass trombone . . . in the next room . . . and get on the microphone louder than anybody else in the whole section."

Micheal Grose discussed "projection . . . this rawness to the sound that you didn't hear up in the gallery" with Dale Clevenger in this TubaPeopleTV interview (give it a listen). In 2007, Scientific American published: Why can an opera singer be heard over the much louder orchestra? (You should get at least one free article. You may need to give them your email.)

My concept of bass trombone sound is "an iron fist in a velvet glove." Too much (or little) of either is a problem – and the ratio varies situationally. Different instruments can seem to project differently. In the "heresy" section of Magic Equipment, I discuss my feelings in this regard – basically, if we hear ourselves less, we play louder – ergo, we project better.

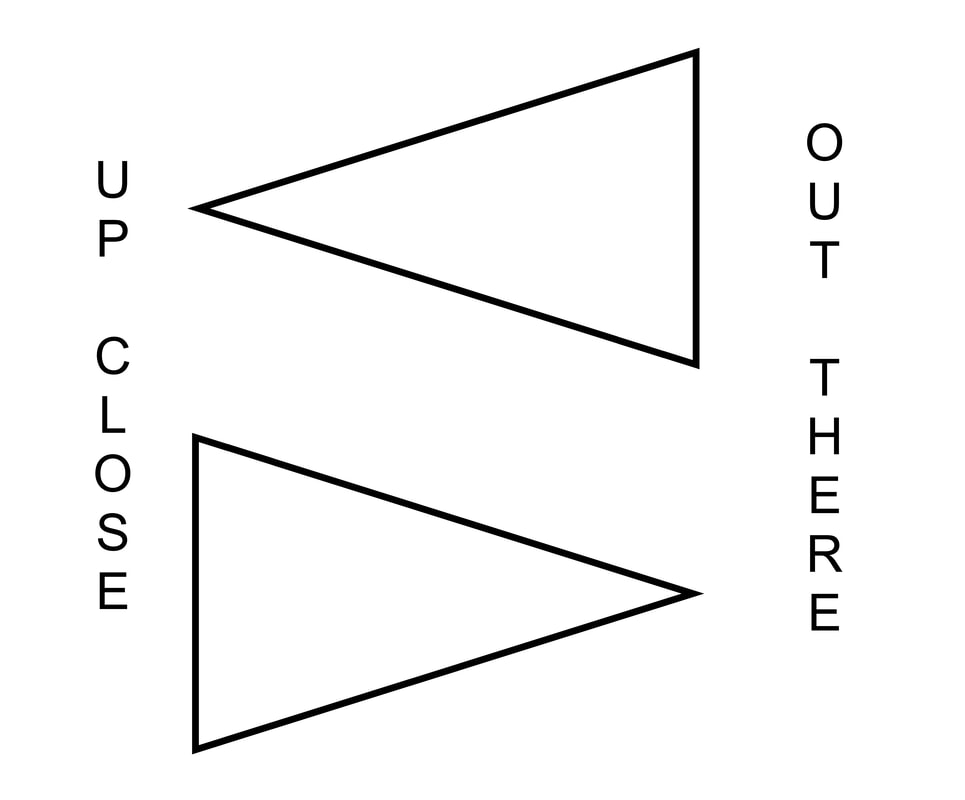

Here is my take on a drawing Jeff did once in a lesson. The idea is that a solid, dense, compact, tone sounds big out in the hall – but a wide, fluffy, "mellow" sound doesn't "get out there."

Ed Kleinhammer once told a student: "If you heard me, I was a failure. You shouldn't have heard a trombone player. You should have heard a great orchestra." – Food for thought.

Another paraphrase from Jeffrey: Frequently, we blend undetectably – below the "texture line." Sometimes, we are noticeably present in the blend – right at the "texture line." And sometimes, we are over the top – very occasionally, way over the top! Remember, Stan Lee said . . .

"Projection" is not necessarily about playing loud. George Roberts was notorious for playing very quietly and bleeding on every mic in the room – or cutting through a roaring big band. Barrett O'Hara (a great bass trombonist in his own right) attributed this phenomenon to the "magic burr" in George's tone. Tommy Johnson called it the "mystery tone." Jeff Reynolds tells a tale about working with George in his response to question #8 in David Brubeck's 2015 Seven Positions interview. And at Lloyd Ulyate’s 70th birthday party, Lew McCreary (another fine player) introduced George by saying, "Here's the only guy who can play the bass trombone . . . in the next room . . . and get on the microphone louder than anybody else in the whole section."

Micheal Grose discussed "projection . . . this rawness to the sound that you didn't hear up in the gallery" with Dale Clevenger in this TubaPeopleTV interview (give it a listen). In 2007, Scientific American published: Why can an opera singer be heard over the much louder orchestra? (You should get at least one free article. You may need to give them your email.)

My concept of bass trombone sound is "an iron fist in a velvet glove." Too much (or little) of either is a problem – and the ratio varies situationally. Different instruments can seem to project differently. In the "heresy" section of Magic Equipment, I discuss my feelings in this regard – basically, if we hear ourselves less, we play louder – ergo, we project better.

Here is my take on a drawing Jeff did once in a lesson. The idea is that a solid, dense, compact, tone sounds big out in the hall – but a wide, fluffy, "mellow" sound doesn't "get out there."